Appendixes

Appendix A

Compost Manufacture on a Tea Estate in Bengal

THE Gandrapara Tea Estate is situated about 5 miles south of the foothills of the Himalayas in North-East India in the district called the Dooars (the doors of Bhutan). The Estate covers 2,796 acres, of which 1,242 are under tea, and it includes 10 acres of tea seed bushes. There are also paddy or rice land, fuel reserve, thatch reserves, bamboos, tuna oil, and grazing land. The rainfall varies from 85 to 160 inches and this amount falls between the middle of April and the middle of October, when it is hot and steamy and everything seems to grow.

The cold-weather months are delightful, but from March till the monsoon breaks in June the climate is very trying.

There are approximately 2,200 coolies housed on the garden; most of these originally came from Nagpur, but have been resident for a number of years. The Estate is a fairly healthy one, being on a plateau between large rivers; and there are no streams of any kind near or running through the property. All drainage is taken into a nearby forest and into waste land. The coolies are provided with houses, water-supply, firewood, medicines, and medical attention free, and when ill they are cared for in the hospital freely. Ante-natal and post-natal cases receive careful attention and are inspected by the European Medical Officer each week and paid a bonus; careful records of babies and their weights are kept and their feeding studied; the Company provides feeding-bottles, 'Cow and Gate' food, and other requirements to build up a coming healthy labour force. As we survey all living things on the earth to-day we have little cause to be proud of the use to which we have put our knowledge of the natural sciences. Soil, plant, animal, and man himself -- are they not all ailing under our care?

The tea plant requires nutrition and Sir Albert Howard not only wants to increase the quality of human food, but in order that it may be of proper standard, he wants to improve the quality of plant food. That is to say, he considers the fundamental problem is the improvement of the soil itself -- making it healthy and fertile. 'A fertile soil,' he says, 'rich in humus, needs nothing more in the way of manure: the crop requires no protection from pests: it looks after itself.' . . .

In 1934 the manufacture of humus on a small scale was instituted under the 'Indore method' advocated by Sir Albert Howard. The humus is manufactured from the waste products of tea estates. All available vegetable matter of every description, such as Ageratum, weeds, thatch, leaves, and so forth, are carefully collected and stacked, put into pits in layers, sprinkled with urinated earth to which a handful of wood ashes has been added, then a layer of broken-up dung, and soiled bedding; the contents are then watered with a fine spray -- not too much water but well moistened. This charging process is continued till the pit is full to a depth of from 3 to 4 feet, each layer being watered with a fine spray as before.

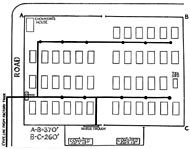

PLATE X:

Bigger image.

Bigger image.

Plan of the compost factory, Gandrapara Tea Estate

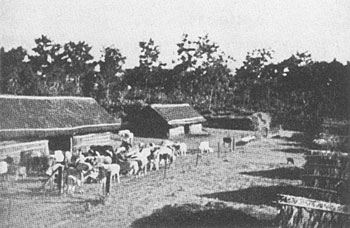

To do all this it was most necessary to have a central factory, so that the work could be controlled and the cost kept as low as possible. A central factory was erected; details are given in the plan (Plate X); there are 41 pits each 31 x 15 x 3 feet deep; the roofs over these pits are 33 by 17 feet, space between sheds 12 feet and between lines of sheds 30 feet; also between sheds to fencing 30 feet; this allows materials to be carted direct to the pits and also leaves room for finished material. Water has been laid on, a 2-inch pipe with 1-inch standards and hydrants 54 feet apart, allowing the hose to reach all pits. A fine spreader jet is used; rain-sprinklers are also employed with a fine spray. The communal cow-sheds are situated adjacent to the humus factory and are 50 by 15 feet each and can accommodate 200 head of cattle: the enclosure, 173 by 57 feet, is also used to provide outside sleeping accommodation; there is a water trough 11 feet 6 inches long by 3 feet wide to provide water for the animals at all times; the living houses of the cowherds are near to the site. An office, store, and chowkidar's house are in the factory enclosure. The main cart-road to the lines runs parallel with the enclosure and during the cold weather all traffic to and from the lines passes over this road, where material that requires to be broken down is laid and changed daily as required. Water for the factory has a good head and is plentiful, the main cock for the supply being controlled from the office on the site. All pits are numbered, and records of material used in each pit are kept, including cost; turning dates and costs, temperatures, watering and lifting, &c., are kept in detail; weighments are only taken when the humus is applied so as to ascertain tasks and tons per acre of application to mature tea, nurseries, tung barees, seed-bearing bushes, or weak plants.

The communal cow-sheds and enclosure are bedded with jungle and this is removed as required for the charging of the pits. I have tried out pits with brick vents, but I consider that a few hollow bamboos placed in the pits give a better aeration and these vents make it possible to increase the output per pit, as the fermenting mass can be made 4 to 5 feet deep. Much care has to be taken at the charging of the pits so that no trampling takes place and a large board across the pits saves the coolies from pressing down the material when charging. At the first turn all woody material that has not broken down by carts passing over it is chopped up by a sharp hoe, thus ensuring that full fermentation may act, and fungous growth is general.

PLATE XI: Composting at Gandrapara

Covered and uncovered pits.

Roofing a pit.

Cutting Ageratum.

PLATE XII: Composting at Gandrapara

Communal cowshed.

Crushing woody material by road traffic.

Sheet-composting of tea prunings.

With the arrangement of the humus factory compost can be made at any time of the year, the normal process taking about three months. With the central factory much better supervision can be given, and a better class of humus is made. That made outside and alongside the raw material and left for the rains to break down acts quite well, but the finished product is not nearly so good. It therefore pays to cut and wither the material and transport it to the central factory as far as possible.

In the cold weather, a great deal of sheet-composting can be done" After pruning, the humus is spread at 5 tons to the acre; and hoed in with the prunings; the bulk of prunings varies, but on some sections up to 16 tons per acre have been hoed in with the humus and excellent results are being obtained.

On many gardens the supply of available cow-dung manure and green material is nothing like equal to the demand. Many agriculturists try to make up the shortage by such expedients as hoeing-in of green crops and the use of shade trees or any decaying vegetable material that may be obtainable; on practically all gardens some use is made of all forms of organic materials, and fertility is kept up by these means. It is significant to note that, for many years now, manufacturers who specialize in compound manures usually make a range of special fertilizers that contain an appreciable percentage of humus. The importance of supplying soils with the humus they need is obvious. I have not space to consider the important question of facilitating the work of the soil-bacteria, but it has to be acknowledged that a supply of available humus is essential to their well-being and beneficial activities.

Without the beneficial soil-bacteria there could be no growth, and it follows that, however correctly we may use chemical fertilizers according to some theoretical standard, if there is not in the soil a supply of available humus, there will be disappointing crops, weak bushes, blighted and diseased frames. Also it will be to the good if every means whereby humus can be supplied to the soil in a practical and economical way can receive the sympathetic attention of those who at the present time mould agricultural opinion.

To the above must be added the aeration of the soil by drainage and shade, and I am afraid that many planters and estates do not under stand this most important operation in the cultivation of tea. To maintain the fertility we must have good drainage, shade trees, tillage of various descriptions, and manuring. Compost is essential, artificials are a tonic, while humus is a food and goes to capital account.

This has been most marked in the season just closing. From October I 938 to April 20th, 1939, there had been less than 1-1/2 inches of rain, and consequently the gardens that suffered most from drought were those that had little store of organic material -- drainage, feeding of the soil, and establishment of shade trees being at fault.

Coolies are allowed to keep their own animals, which graze free on the Company's land, and the following census gives an idea of what is on the property: 133 buffaloes, 115 bullocks, 612 cows, 466 calves, 21 ponies, 384 goats, 64 pigs: in all, 1,795 animals.

During the past two years practically no chemical manure or sprays for disease and pest-control have been used, the output for the past year of humus was about 3,085 tons, while a further 1,270 tons of forest leaf-mould have been applied. The cost of making and applying the former is Rs.2/8/6 per ton, and cost and applying forest leaf-mould is Rs.1/3/9 per ton.

The conversion of vegetable and animal waste into humus has been followed by a definite improvement in soil-fertility.

The return to the soil of all organic waste in a natural cycle is considered by many scientists to be the mode of obtaining the best-tasting tea, and to resisting pest and disease.

Nature's way, they claim, is still the best way.

Gandrapara Tea Estate,

Banarhat, P.O.

J.C. Watson.

18 November, 1939.

Next: B. Compost Making at Chipoli, Southern Rhodesia

Back to Contents

To Albert Howard review and index

Back to Small Farms Library index