HOME HYGIENE LIBRARY CATALOG GO TO NEXT CHAPTER

Abstinence from food may mean missing one meal, or it may mean going without food until death results from starvation. Missing one meal produces no organic or chemical changes in the body; in starvation, many changes occur. It is necessary to know that different changes occur at different stages of the period of abstinence and that the changes at different stages are of different, even opposite, character. For example, in women and female animals, atrophy of the mammary glands is seen in starvation, but in fasting, there is only a loss of fat. In the early stages of abstinence in young guinea pigs, the pancreas, like the other internal organs, is in general more resistant to loss of weight. Pancreatic losses in the early stages of abstinence are relatively slight, while in advanced stages, that is, in starvation, pancreatic loss (atrophy) is extreme, being, as a rule, relatively greater than that of the entire body. Many examples of similar differences will be given throughout the pages of this book.

There is naturally and necessarily a loss of weight when man or animal ceases to eat and if food is abstained from long enough, death results from too great loss. In discussing the differences between fasting and starving we made use of Morgulis' three stages of the inanition period--from the omission of the first meal until its ending in death. In general, in both birds and mammals, the loss of weight is greatest during the first third of the inanition period, least in the second third, and intermediate in the last third, although this final acceleration of loss is variable or even absent.

In all animals, from worms to man, the various organs and tissues of the body differ very greatly in their rates of loss while fasting and starving. In general, it may be said that most of the soft tissues of the body lose weight during a fast, but they lose at varying rates. Instead of a uniform wasting of the body's resources, biologically important organs are sustained at the expense of less important ones.

Structural changes during fasting are largely those that result from loss of weight. At death from starvation the amount of weight lost may amount to fifty to sixty per cent. No such losses are registered in a fast. As before pointed out, individual organs or tissues, show a very unequal emaciation, some living at the expense of others.

It will be interesting to note some of the losses and changes which occur during the fast. In death by starvation the following losses have been observed by some investigators:

Fat 91% Spleen 63% Muscle 30% Blood 17% Liver 56% Nerves ???

Yeo's physiology gives the estimated losses that occur in death from starvation as:--

Fat 97% Spleen 63% Muscle 30% Blood 17% Liver 56% Nerve Centers 000

According to Chossat, the losses sustained by the various tissues in starvation are as follows:-

Fat 93% Nerves 2% Muscles 43% Pancreas 64% Liver 52% Spleen 70% Blood 75%

Chossat's table was made from animal experimentation, and agrees very well with the observations of others, except in the loss of blood. Others have given this as less than twenty per cent. The International Encyclopedia, under "fasting," gives a table showing the losses sustained by an animal while fasting for thirteen days. This table gives the loss of blood for this time as 17%. and the loss to the brain and nerves as none.

It will be observed that during the fast the tissues do not all waste at an equal rate; those that are not essential are utilized most rapidly, those least essential less rapidly and those most essential not at all at first and only slowly at the last. Nature always favors the most vital organs. The fat disappears first, and then the other tissues in the inverse order of their usefulness. The essential tissues obtain their nourishment from the less essential, by enzymic action, a process which has been termed autolysis.

From these tables it will be seen that the brain and nervous system continue intact (retain their structural and functional integrity) until the last and retain the inherent power to maintain their nutrition unimpaired, although every other tissue has wasted beyond repair; and that the blood even in the most extreme cases, does not show extraordinary depletion.

Such physiological facts would seem to argue that nerve and blood supply throughout the body are virtually normal during a fast; and that the human body is, in reality, a veritable organization of assimilable food elements dominated by a self-maintaining intelligence which is capable of preserving relative structural integrity and physiologic functional balance even when all food is withheld for considerable intervals.

Only in a very special sense does the body "start eating itself" when one begins to fast. It never consumes its tissues indiscriminately, but, true to its rule of always favoring its most vital organs, it uses up the least useful tissues first. Selective action is exercised from the beginning and the most rigid economy is exercised in appropriating its food reserves in sustaining the heart, lungs, brain, nerves and other vital organs. Even the respiratory muscles are more carefully guarded than the other muscles of the skeleton.

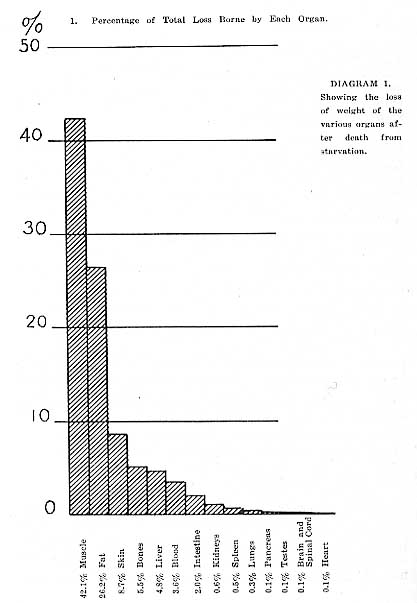

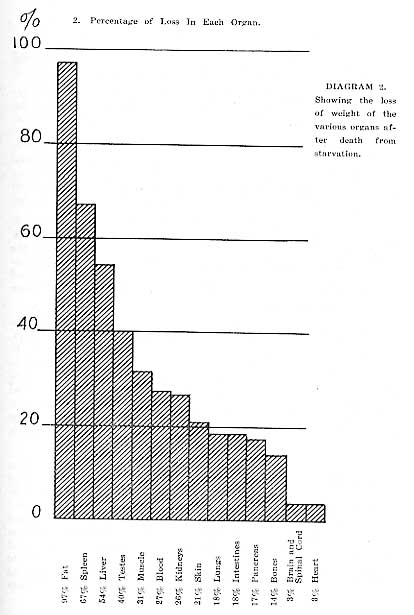

The accompanying two diagrams, Nos. 1 and 2, are after Voit. Diagram 1 shows the percentage of the total loss of the body borne by each organ in death by starvation, while diagram 2 shows the percentage of loss in each organ under the same circumstances. These tables also include the proportion which the loss in each bears to the weight of a similar animal killed in good condition.

The careful student will bear in mind that most of the actual tissue losses shown by these tables occurred in the last third of the inanition period--the period of starvation proper--and do not occur during the fasting period.

While table 1 shows that the musculature of the body supplies the greatest loss of weight, the actual loss to the muscles only reaches 21 per cent of the total muscular substance (chiefly the superficial muscles), while, though the actual proportion of weight lost is less, 97 per cent of the fat present is used up. The other organs which lose much of their weight are the spleen with 67 per cent; the liver with 54 per cent, and the testes with 40 per cent. The central nervous tissue and the heart supply only 0.1 per cent of the total loss, and 3 per cent of their actual substance.

A closer and more detailed view of the losses to the more important organs and tissues will help us to better understand the subjects we are here dealing with.

The blood diminishes in volume in proportion to the decrease in the size of the body so that the relative blood-volume remains practically unchanged during a fast. The quality of the blood is not impaired; indeed, an actual rejuvenation of the blood may occur.

Dr. Rabagliati pointed out that the first effect of the fast is to increase the number of red blood corpuscles, but if persisted in sufficiently long, decrease them. The increase of erethrocytes, during the early part of the fast, he regarded as due to improved nutrition resulting from a cessation of overeating. This increase in red blood cells has been repeatedly noted in anemia. The decrease is seen only after the starvation period is reached.

Prof. Benedict says: "Senator and Mueller in reporting the results of their examinations of the blood of Celti and Briethaupt, noted an increase in the red blood corpuscles with both subjects. In a later examination of Succi's blood, by Tauszk, the conclusions reached were (1) that after a short period of diminution in the number of red blood corpuscles there is a slight increase: (2) that the number of white blood corpuscles decreases as the fast progresses; (3) the number of mononuclear corpuscles decreases: (4) the number of eosinophiles and polynuclear cells increases; and finally (5) that the alkalinescence of the blood diminishes."

Later experiments agree almost entirely with these results. The Carnegie Institute Bulletin, 203, pages 156-157 says: "The results of the above studies (of fasting) are conspicuous rather from the absence than the presence of striking alterations in the blood picture," and adds, "The final conclusions as to the effects of uncomplicated starvation on the blood to be drawn from the results of examination of Levanzin, are: In an otherwise normal individual, whose mental and physical activities are restricted, the blood as a whole is able to withstand the effects of complete abstinence from food for a period of at least 31 days (the length of Levanzin's fast), without displaying any essentially pathological change." Structural and morphological changes do not occur in normal blood cells during a fast.

Pashutin records the case of a man who died after four months and twelve days (132 days) without food and says that two days before death the blood contained 4,849,400 red and 7,852 white corpuscles in one cu. mm. Prof. Stengel says: "The blood in starvation preserves its corpuscular richness surprisingly, even after prolonged abstinence."

Fasting for only one week will increase the number of red cells in an anemic person. Medical and laboratory experimenters have conducted all their experiments on healthy men and animals, hence they have not been permitted to observe the regenerating effects of fasting upon the blood. Their statement that "human blood is relatively resistant during fasting" is true, but it does not tell the whole truth. Their statement that "there is a tendency to increase in the red cell count" is also true, but even this does not tell the whole truth.

Jackson says: "During human inanition, the erythrocyte (red cell) count is often within normal limits, but sometimes increased (especially in total inanition and earlier stages), or decreased (especially in chronic and late stages). In animals, the red cell count appears more frequently increased in the earlier stages of total inanition, often decreasing later. In hibernation, the erythrocyte count is variable."--Inanition and Malnutrition--p. 239.

Normal blood contains from 4,500,000 to 5,000,000 and as high as 6,000,000 in healthy young men, red cells per cu. mm. and 3,000 to 10,500, with a probable average of 5,000 to 7,000 white cells per cu. mm.

Dr. Eales' blood was examined June 20, 1907, the first day of his fast, by Dr. P. G. Hurford, House Physician to Washington University Hospital, St. Louis. It showed the following:

Leucocytes 5,300 per cubic millimeter.

Erethrocytes 4,900,000 per cubic millimeter.

Hemoglobin 90%.

A blood test was again made on July 3, the 14th day of his fast, by Dr. S. B. Strong, House Physician, Cook Gouty Hospital, which showed:

Leucocytes 7,000 per cu. mm.

Erethrocytes 5,528,000 per cu. mm.

Hemoglobin 90%.

It will be noted that the blood has materially improved on the fast.

A third examination of Dr. Eale's blood made by Dr. R. A. Jettis, of Centralia, Ill., on August 2, showed:

Leucocytes 7,328 per cu. mm.

Erethrocytes 5,870,000 per cu. mm.

Hemoglobin 90%.

A further improvement in the condition of his blood is here seen.

Laboratory investigators have reported an increase in the red cells of healthy fasters with a decrease in white cells. In anemia, fasting often results in an increase in the number of red blood corpuscles to more than twice their former number, with a concomitant decrease in the number of white blood cells. In a talk in Chicago a few years ago, Dr. Tilden said: "Cases of pernicious anemia taken off their food will double their blood count in one week." Dr. Weger reports a case of anemia in which a 12 days' fast resulted in an increase of the number of red cells from 1,500,000, to 3,000,000; hemoglobin increased fifty percent, and white cells were reduced from 37,000 to 14,000.

Wm. H. Hay, M.D., in his Health Via Diet tells of caring for 101 cases of progressive pernicious anemia, during twenty-one years by fasting, correct diet and colonic irrigation. Of these 101 cases he says that 8 failed of initial recovery. Part of the recoveries were made permanent by right living. Some of those who relapsed resorted once more to the fast and again recovered.

The first 13 cases of progressive pernicious anemia which Dr. Hay placed upon a fast recovered in from two weeks to longer. The fourteenth case, being in a dying condition when she arrived, did not recover. Dr. Hay says: "The blood during a fast undergoes no visible changes as to cell count unless markedly abnormal when the fast is begun in which case there is a return to normal." * * * "For most of two weeks (in progressive pernicious anemia) the red, erethrocyte, count continues to fall before there is a regeneration in the blood-making organs; then gradually the microscopic picture begins to show round erethrocytes with regular edges, no crenations or irregularities, and soon there is noticeable increase in number of these with gradual disappearance of the adventitious cells present in the beginning.

"Not unusually there is a gain during the succeeding two weeks that brings the total back to the normal five million erethrocyte count, even though this may have been at, or below, one million in the beginning.

Von Norden says: "The blood atrophies." This is true of the starvation period, not of fasting proper. Much confusion will be avoided if the student will keep clearly in mind the fact that destructive changes occur only after the exhaustion of the body's reserves. Von Norden, Kellogg and others never tired of detailing the destructive changes that occur in the body during "starvation." Indeed, they were right in their details if they had used the term starvation properly. But they believed that the changes seen in starvation belong, also, to the fasting period. They made no distinction between the two processes. Later, investigators have corrected this old mistake, although few writers on the subject in our encyclopedias and standard works seem to have heard of this fact.

The decreased alkalinity due to prolonged fasting is often urged against it. It is contended that fasting produces acidosis. Fasting does not produce acidosis and the decreased alkalinity is never great enough, even in the most protracted fasts, to result in any deficiency "disease," unless the frequent cases of impotency are to be regarded as due to a loss of vitamins or mineral salts. The blood rapidly regains its normal alkalinity after feeding is resumed and no damage is done.

Mr. Macfadden says: "It has been said that an acid condition of the blood, fluids and tissues (acidosis) is sometimes brought about by fasting. I cannot concede that this is ever the case, in true fasting. As a matter of fact, all the evidence seems to prove that as Dr. Haig expressed it, 'fasting acts like a dose of alkali.' If there is acidity in the system, fasting will remove it and restore the chemical balance of the system. Therapeutic fasting never created acidity, but on the contrary, removes that state when existing. Of course protracted starvation may do so, but then, who ever advised starvation.

"The medical as well as the general idea is that starvation begins practically immediately when meals are discontinued. The impression is that at once the blood and solid structures of the body begin to break down, that organic destruction has begun. Such is far from the case, as results have proved in scores (thousands) of cases. The vital cells of the organs and glands--those doing the active physical and chemical work of these parts--do not begin to disintegrate until actual starvation begins."

During a fast the body lives on its reserves. Starvation does not begin until these reserves are exhausted. What is more, these reserves contain sufficient alkaline reserves to prevent the development of so-called acidosis.

Dr. Weger says: "Varying degrees of acidosis were often in evidence during fasting. These we consider physiological. Except in very rare instances, the active symptoms are of short duration and easily overcome without interfering with or curtailing the fast." He describes the "symptoms of acidosis during a fast" as "lassitude, headache, leg and back ache, irritability, restlessness, redness of the buccal (mouth) mucous membrane and tongue, sometimes drowsiness, and also a fruity odor to the breath."

These symptoms develop at the beginning of the fast and grow less and less as the fast continues, until they cease altogether. If fasting produces acidosis the evidence should increase as the fast progresses. I believe that all of these symptoms may be explained without regarding them as evidences of acidosis. They result, I believe, from the withdrawal of the accustomed stimulation--coffee, tea, chocolate, cocoa, alcohol, tobacco, meat, pepper, spices, salt, etc., etc.--and are identical with these same symptoms when they develop in the man or woman who gives up coffee or tobacco, but who does not cease to eat. I do not think the "fruity odor" of the breath can be explained in this manner. However, in thousands of fasts I have conducted, I have never met with such a phenomenon--the breath in all cases being very foul and much like that of the fever patient or like the bad breath most people have, only much intensified.

Dr. Weger, himself, says: "Fasting is not and cannot be the cause of acidosis, for the symptom-complex of acidosis is quite common in full-fed plethoric individuals, in whom the makings of acidosis exist as a result of an over-crowded nutrition. It is true that symptoms of acidosis frequently occur and make patients decidedly uncomfortable during the early stages of the fast. However, these symptoms are due to excessively rapid consumption of the body fat--a catalytic action--and the checking of elimination because of sub-oxidation. In less than ten per cent of such cases do these discomforts last more than three or four days. This indicates to us that the acidosis, as such, was a latent condition that would be excited into activity by any other equally potent provocative. This condition is analogous to a crisis which might occur in the form of an acute disease. The sicker one is made by a fast, the greater the need for it."

In general I agree with these words of Dr. Weger, but I have noted these supposed symptoms of acidosis in cases where there was no rapid breaking down of tissue, and in cases in which physical activity was sufficient to keep up normal oxidation and in which elimination was normal or super-normal. I do regard these symptoms as being part of a crisis and as beneficial in outcome. I have noted repeatedly that the more severe are these symptoms, the more benefit the patient receives from the fast and the sooner do these benefits manifest.

The exquisite texture and delicate pink color of the skin that develop while fasting attests the rejuvenation the skin undergoes. The clearing up of blotches and blemishes with, even the disappearance of finer lines in the skin, are particularly significant as showing the benefits the skin derives from a period of physiological rest.

That the circulation of the skin is much improved by a period of physiological rest is demonstrated by the way that the blood thoroughly and instantaneously responds to a pinch of the skin. This true "pink of condition" is invariably observed toward the end of the fast and indicates the greatly improved condition of the body. This is to say, the improvement in the skin mirrors the improvement that has taken place within.

There is no evidence of any loss to the bones during a fast. Indeed, as will be shown in another chapter, they may even continue to grow while fasting.

When we observe the marrow of the bones, however, we notice a remarkable change. Marrow is stored up food and readily drawn upon for nourishment when no food is eaten. In starved calves, for example, the marrow is reduced to a watery mass. This, amount, of change, however, does not occur during an ordinary fast.

Teeth are specialized bones and are subject to the same laws of nutrition as other bones of the body. In certain quarters it is claimed that fasting ruins the teeth. The claim is not true and no one with a knowledge of fasting makes it. No evidence exists that there is any loss to the bones or teeth during a fast. There is an apparent decrease in the amount of organic matter in the teeth of starved rabbits, but the teeth of these animals grow continuously throughout life, and Prof. Morgulis suggests that this decrease may be due simply to a deficiency of building material.

Jackson says: "Like the skeleton, the teeth appear very resistant to inanition. * * * In total inanition, or on water alone, the teeth in adults show no appreciable change in weight or structure."

There is no truth in the notion that fasting injures the teeth. On the contrary, repeated tests and experiments in the laboratory have shown that the bones and teeth are uninjured by prolonged fasting.

I have conducted thousands of fasts and I have never seen any injury accrue to the teeth therefrom. No one makes a trip to the dentist after a fast who would not have gone there had the fast not been taken. Mr. Pearson records that at the end of his fast, "teeth with black cavities became white and clear, all decay seemed to be arrested by the fast, and there was no more tooth-ache."

The only effects upon the teeth which I have observed to occur during a fast are improvements. I have seen teeth that were loose in their sockets become firmly fixed while fasting. I have seen diseased gums heal up while fasting. But I have never, at any time, observed any injurious effects upon the teeth during or after a fast, regardless of the age of the faster and the duration of the fast. This applies only to good teeth. Fasting does sometimes cause fillings to become loose.

Although I have always regarded the loosening of fillings in teeth as due to the extraction of the salts of the bad teeth, some of my students have brought up the question: Is the loss of the filling due to an effort of Nature to dislodge a foreign body preparatory to healing the tooth? This question is worthy of study.

The brain and nervous system are supported and lose little or no weight during a fast, while the less important tissues are sacrificed to feed them. They maintain their power and ability to control the functions of the body, as well, (and even better) during the most prolonged fast, as when fed the accustomed amounts of "good nourishing food." Relatively to the rest of the body, the brain and nervous system increase as the fast continues, due to the fact that little or none of their substances are lost.

The spinal cord loses less than 10 per cent in death by starvation--the brain nothing. There are almost no structural changes in the brain and cord even in starvation.

"In general," says Jackson, "the brain appears relatively resistant to the effects of both total and partial inanition. Usually little or no loss in weight or changes in gross or microscopic structure are apparent. In advanced stages of starvation, however, and especially in types of partial inanition (beri beri, pellagra), involving neural or psychic disturbances, there are well-marked degenerative changes in the nerve cells."--Inanition and Malnutrition, p. 173.

Here, again, we note a confusing of the effects of actual starvation with those of inadequate diet so that the statement is a bit misleading. We must also emphasize again that losses seen in starvation are not seen in fasting. It is well always to keep the distinction between fasting and starving in mind.

The losses to the kidneys are insignificant and are usually much less than that of the body as a whole. In the young the kidneys are even more resistant to loss of weight.

The losses to the liver during a fast are largely water and glycogen. Usually the liver loses more in weight relative to the rest of the body than the other organs, especially in the earlier stages, due to the loss of glycogen and fat.

Jackson says: "In uncomplicated cases of total inanition, or on water only, the lungs are usually normal in appearance. The loss in weight of the lungs in such cases is usually relatively less than that in the body as a whole, though sometimes equal to, or even relatively greater than, that of the entire body. In the young, the lungs usually appear more resistant to loss in weight."--Inanition and Malnutrition, p. 361.

That the lungs are greatly benefited by fasting is shown by their recovery from "disease," even tuberculosis, during a period of abstinence. Shorter fasts are usually required in lung "diseases," than in "disease" of other organs and Carrington thinks this is due to the fact that lung tissue "possesses the inherent power of healing itself in a far shorter time, and more effectually, than any other organ which may be diseased."

It has been shown by investigators that the skeletal muscles may lose 40% of their weight, whereas, the heart muscle loses only 3% by the time death from starvation is reached. The decrease in the size of the muscles extends also to their cells, which similarly decrease in size. Probably there is not an actual lessening of the number of muscle cells in a fast of ordinary duration, but only a consumption of fat, glycogen, and lastly some of the muscle protein and a lessening of the size of the cells. This loss of fat and muscle might occur at any time without damage to health.

In general the skeletal muscles are affected earlier and more intensely than the smooth muscles. There seems to be no actual decrease in the number of muscle fibers, but only a diminution in the size of their cells. The cells are merely reduced in size but remain perfectly sound.

In frogs and salmon, fat is stored in the muscles during the eating period, and consumed during the fasting and hibernating period. The decrease in size is due to a loss of fat, not of muscle. Much the same phenomena are often observed in fasting patients.

The heart muscle does not diminish appreciably, deriving its sustenance from the less essential tissues. Its rate of pulsion varies greatly, rising and falling as the needs of the system demand. Studying the respiration rate, Benedict noted various minor fluctuations and arrived at the conclusion that "at least during the first two days of the fast, the pulse rate is much more liable to fluctuations than the respiration rate." That fasting benefits the heart is certain from the results obtained in functional and even in organic heart "disease" during a fast. This arises from three chief causes--namely, (1) it removes the constant stimulation of the heart; (2) it takes a heavy load off the heart and permits it to rest; (3) it purifies the blood thus nourishing the heart with better food.

The heart that is pulsating at the rate of 80 times a minute pulsates 115,200 times in twenty-four hours. Shortly after the fast is instituted, the heart rate decreases and, while it may temporarily go much below 60 pulsations a minute, it ultimately settles at 60 beats a minute and remains there for the duration of the fast. This is 86,400 pulsations in twenty-four hours, or 28,800 fewer pulsations each day than it was doing before the fast.

This represents a decrease of twenty-five per cent of the work of the heart. The saving in work is seen not merely in the reduction of the number of pulsations, but also in the vigor or force of the pulsations. It all sums up to a real vacation--a rest--for the heart. During this rest the heart repairs its damaged structures and replenishes its tissues.

As shown elsewhere, the heart muscle loses only three per cent by the time death occurs from starvation. As in other essential tissues the loss of this small per cent occurs after the exhaustion of the body's nutritive reserves--that is, during the starvation period. This ability of the body to nourish the heart during a prolonged fast is a sure guarantee against damage to the heart resulting from the fast.

Reviewing the chief historical cases of fasting with reference to the pulse beat, Benedict shows that in some cases the pulse remained "normal," and in others it rose or fell. As a result of his review of these cases and of his own series of short experimental fasts, he arrived at no definite conclusions. Carrington says: "That the heart is invariably strengthened and invigorated by fasting is true beyond a doubt. * * * I take the stand that fasting is the greatest of all strengtheners of weak hearts--being, in fact, its only rational, physiological cure." He attributes the benefits that accrue to the heart while fasting to increased rest, a purer blood stream and absence of stimulation.

The recovery of the heart from serious impairment during a fast ( I have had complete and permanent recoveries in what were thought to be incurable organic heart affections), proves that the added rest the fast affords the heart and the general renovation of the body, enable it to repair itself.

Dr. Eales says: "Instead of the heart growing weak during a fast it grows stronger every hour as the load it has been carrying is lessened." High blood pressure is invariably lowered and this removes a heavy load from the heart.

On the 15th day of his fast, friends of Dr. Eales brought him the news account of the sudden death of a man in Washington, D. C., while on a fast. The papers attributed the death to the fast, and friends of Dr. Bales warned him of heart failure. Dr. Bales replied to their warnings: "This man's death was not caused by the fast, in fact the fast lengthened his life, for if he had not been fasting he would undoubtedly have died a week or more earlier. He probably resorted to the fast to save his life, but it was too late; his light was too nearly burned out when he started. How many times do we hear of dying after a full meal, when making an after-dinner speech or sitting in their chairs and expiring! That, of course, is regular, but to die when the heart is resting and doing less work than when one is eating, when it is simply worn and run down from overwork, is always attributed to fasting, if the person is fasting at the time of death."

Of the many thousands who die yearly of heart trouble, probably not more than three or four are fasting at the time of their death. In my own practice one death from "heart failure" has occurred during a fast. The patient had been greatly overweight for years, with high blood pressure, nervous troubles, glaucoma, and gave a history of diabetes. Quite naturally the failure of her heart was attributed to the fast and the fact that people in her condition die every day from "heart failure" who have not been fasting, but feeding, escapes notice. Wm. J. Bryan, who never fasted, ate a hearty meal, went to bed for an afternoon nap and never woke up. These things occur daily.

The woman was many pounds overweight at death and there could be no suggestion of starvation in this case. There were ample food reserves left in her body for another forty to fifty days of fasting.

I attribute the collapse of the heart in the above case to fear. That fear was present was manifest. That the woman had the suggestion of starvation and death dinned into her ears every day of her fast and had the suggestion intensified after the heart became affected is certain. Sudden deaths from fear, shock, etc., are not unknown nor even uncommon.

"How many times," asks Dr. Eales, in discussing the effects of fear in the fast, "have we heard of sad news producing prostration or a fit of sickness; a mother's milk becoming poison during a fit of anger causing sickness to her nursing babe, and in some instances even death?"

Again he says: "I find that so long as the mind is free from worry and fear there is not a particle of danger. It is only when the subconscious mind has suggestions of weakness and fear that the body or any of its organs become weak."

Jackson says "that in the early stages of inanition" in young guinea pigs "the pancreas (like the other viscera) appears in general more resistant to loss in weight" and that "the pancreatic losses in the early stages of inanition" are "relatively slight," while in "advanced stages" of inanition the "pancreatic atrophy is extreme, being as a rule relatively greater than that of the entire body." He also says: "upon feeding after inanition, the pancreas recuperates rapidly and is soon restored to normal size and structure."

In humans the pancreas becomes small and firm during inanition. Cases are reported in which the pancreas appeared normal after death by starvation. Other cases are reported with considerable pancreatic destruction. Probably there were other causes than starvation at work in these latter cases.

The losses to the spleen during a fast are chiefly water. In starvation resulting in death, the spleen may lose 67 per cent of its total weight.

A classical example of the way in which fasting permits the stomach to rejuvenate itself is that of Dr. Tanner. He suffered for years with dyspepsia before his first fast. Indeed, it was this suffering that followed every meal that caused him to refrain from eating in order to miss the distress. So remarkably did his stomach repair itself during its period of rest that he was able, very foolishly, of course, to eat "sufficient food in the first twenty-four hours after breaking the fast to gain nine pounds, and thirty-six pounds in eight days, all that I had lost." Although this was a rash procedure, the doctor suffered no apparent ill consequences from it. We cannot approve of such eating following a fast, but cite his example to show what a formerly weakened and dyspeptic stomach can do after a period of fasting.

A stomach rejuvenated through rest returns spontaneously to the normal performance of its function. A weak and dyspeptic stomach resumes normal function after a fast. This alone is sufficient to prove the strengthening results of a rest for the stomach. Both its muscles and its glands are rejuvenated by a period of rest.

It is often objected that fasting permits the stomach to collapse and that it so weakens the stomach that it will no longer be able to digest food. Most stomachs are so weakened by the overwork that results from our national habit of over-eating that the rest that fasting affords it is just what the stomach needs most.

Fasting provides a rest for the stomach, thus giving it an opportunity to repair itself. Morbid sensibilities are overcome, digestion is improved, a distended and prolapsed stomach shrinks and tends to resume its normal size, ulcers heal, inflammation subsides, gastric catarrh is eliminated and the appetite tends to become normal.

The chemical changes which occur in the fasting body are as remarkable as anything that we have described previously. It is quite natural that the fasting body loses some of its substances, but it does not lose all of its elements at the same rate and, what is most remarkable, there occurs a redistribution of some of these, due to the urgent need for preserving the integrity of the vital organs.

The fasting body does not lose its inorganic constituents--minerals--as rapidly as it loses the organic constituents--fats, carbohydrates and proteins. It hangs on to these precious minerals while throwing away its excess of acid-forming elements. The more valuable the material the less of it is lost.

The muscles and blood lose relatively much of their mineral constituents, especially is there a decrease in the percentage of sodium, while considerable mineral substances accumulate in the brain, spleen and liver. There is, then a mere shifting of mineral substances from one part of the body to another. While sulphur and phosphorus diminish in the fasting muscles about as rapidly as do the proteins, there is an increase in the amount of calcium in these organs. There occurs an increase in the percentage of potassium in the soft parts of the body taken as a whole, during the fast. These facts show that potassium salts and calcium salts are not lost as rapidly as some of the other of the body's elements. The excess of iron that may be contained in the diet is taken to the cells of the liver and stored by these. It is probable that the iron set free by the breaking down of the red cells is also stored in the liver and spleen, at least it is not excreted in any great amount. The body's iron reserve, in the form of hematogen, is relatively large.

That the body possesses considerable iron reserve, even in pernicious anemia, is shown by the great and rapid blood regeneration and great increase in hemoglobin and red cells during a fast in these cases. During the fast, the iron liberated by the breaking down of tissue is retained in the body and is not thrown away. Considerable iron and proportionately other necessary elements are consumed during the fast, although the body stores much of its iron in the spleen, liver, marrow cells and in the increased number of red blood cells. The fact that enforced fasting in non-hibernating animals produces the same variable results as those produced by abstinence during hibernation, shows that there is no more danger to the non-hibernating animal than to the hibernating kind. The chief difference is that the non-hibernating animal is likely to be more active while fasting but seldom as active as the Alaskan fur-seal bull during the mating season. The hibernating animal is also likely to possess a greater store of reserve food at the outset.